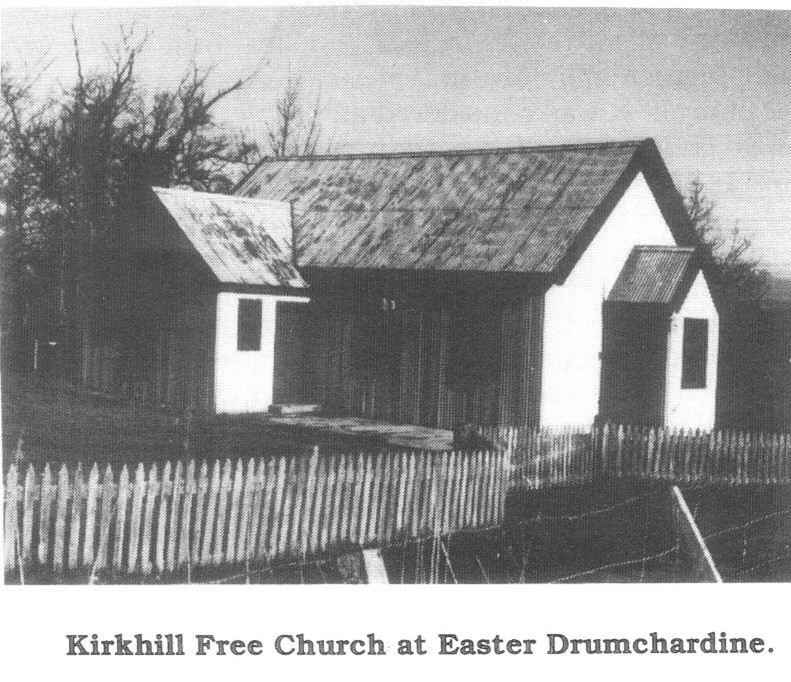

Kirkhill Churches – (location 11)

Two parishes (Wardlaw and Farnua) joined in 1618 to become Kirkhill Parish. The original Wardlaw Church was in Dunballoch, but moved in the medieval period to Kirkhill. The current Wardlaw Church was built in 1790 with later additions. No church survives at Farnua (Kirkton) though the cemetery, enclosed in 1811, can be seen. Several Free Churches were built in the parish after the Disruption of 1843, including the masonry church at Inchmore. When most of the congregation joined the United Free Church in 1900, others built the corrugated iron (‘tin’) church pictured above, now demolished.

Image: courtesy Charlie Gair Collection

Wardlaw Mausoleum (location 12)

Wardlaw Mausoleum was built in 1634 by the Lovat Frasers as their private burial place. It had low walls and a thatched roof. The mausoleum was remodelled in 1722 by Simon Lord Lovat (‘The Old Fox’). His lead coffin (but not his body) and those of his family are in the crypt. In 1827 the Lovats moved their burials to the new Catholic church at Eskadale and the mausoleum fell into disuse. It was restored in 1998 by Wardlaw Mausoleum Trust.

Kirkhill Estates (location 13)

The area has been dominated by clan Fraser from the medieval period, with Fraser of Lovat the largest landowner. Each generation of laird helped shape the landscape in ways which are still evident today. Many of the surviving large houses date to the around 1800, with later additions. In the 1870s, when the Ordnance Survey made its major survey of Britain, the major landowners were Frasers of Lovat, Achnagairn, Lentran, Reelig, Bunchrew, and Donald Cameron of Clunes and J.P.B. Biscoe of Kingillie – though these properties had also been in Fraser hands earlier.

Image: Achnagairn House by Craig Wallace on Geograph.org uk

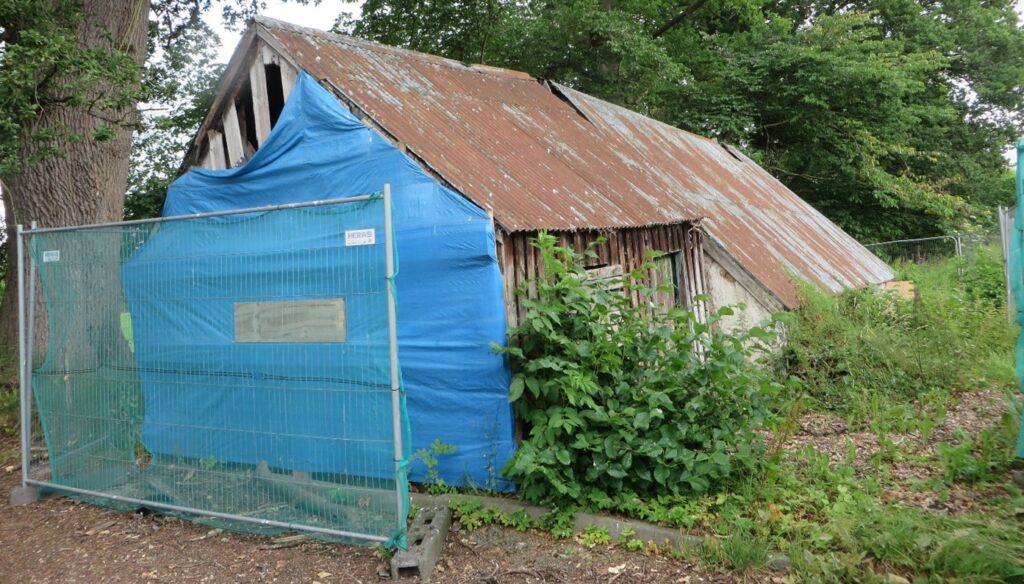

Groam cottage (location 14)

Groam Cottage in Kirkhill was built about 1700. It is a very rare example of a ‘cruck-frame’ cottage where ordinary folk lived. Originally with a thatched roof, the tin roof and an iron range were added about 1900. We are told that the MacDonalds who lived there in 1746 gave refuge to two Jacobites fleeing from the Battle of Culloden. The family moved out in 1950 but their furniture and decorations are still there. The cottage is Grade ‘A’ listed and is owned by Highland Council. It is hoped to restore it and open it to the public.

Posy ring (location 15)

This gold ring was found in the Kirkhill area. It probably dates to the 17th century. The inscription inside the band reads ‘Grace mee, with acceptance’. Posy rings were love tokens, but also gifted to friends and families. The ring is in Inverness Museum.

Schools (location 16)

A number of schools have existed in Kirkhill Parish, with the earliest we know of dating from 1682. Before 1872 schools were established by the church, by charities and privately. Examples are known from Kirkhill, Inchberry, and Milifiach. There is also evidence of a girls’ industrial school. School log books and other accounts survive for the parish. At Inchberry the headteacher James Fraser, did a ‘moonlight flit to America’ in 1834. Following the Education Act of 1872 there were three new schools built in the parish at Inchmore, Knockbain and Kirkton. Today there is only one at Kirkhill.

Image: Headmaster’s room from Knockbain School, now in Highland Folk Museum ©Ronnie Leask, geography.org.uk

Hugh Fraser, Schoolmaster (location 17)

In the 1820s and 1830s the community was rocked by a scandal concerning schoolmaster Hugh Fraser. He was accused of ’immoral and scandalous behaviour’, ‘corrupting youths under his care’, ‘concealment of pregnancy’ with a local woman (whom he married) and a range of other charges. Fraser replied that the charges were baseless and that he was a victim of a conspiracy by those with ‘wealth and power’. Many ordinary folk of the village signed a petition in his support. The details are documented in Kirk records and newspaper accounts. Despite the Church action, he remained a schoolmaster, and his 1864 tombstone pays tribute to his 45 years of service.

Yairs (location 18)

Yairs are fish traps. A stone arm extends out from the shore into a channel, an oblique hook forming an ebb tide pool trap. Stone bases of yairs can be seen along coastlines. Wooden posts and wattle panels designed to stop migrating salmon or sea trout leaping out only rarely survive. Yairs were banned in some areas of Scotland in the 1860s because the salmon stocks dwindled. Several yairs can be seen at low tide along the coast between Lentran and Phopachy and at Bunchrew, including this double example at Whinbrae.

Image by Jim Bone, © Highland Council

Slavery (location 19)

The Highlands of Scotland were involved in the slave trade in a number of ways, primarily through the ownership of plantations but also providing tradesmen, sea captains, overseers and businesses. This shameful history of the Highlands is now becoming better known. Many of the estate owners in the Aird, predominantly Frasers, had plantations in Guyana and the Caribbean, often in partnership. In Kirkhill parish, for example, Clunes, Reelig, Fingask, Achnagairn, Newton, Kingillie and Inchberry were all involved. Fortunes varied but some were able to build mansion houses on their profits. Others lost money, and some their lives.

ARCH Kirkhill Heritage Project Home Page

Panel 1 – Mesolithic to Chalcolthic & Bronze Age (c8000BC – c800BC)

Panel 2 – Iron Age to Norse/Medieval (c800BC – 1560AD)

Panel 4 – Reformation to Industrial Revolution (c1560 – Present day) cont.

Panel 5 – Charlie Gair Photographic Collection – People

Panel 6 – Charlie Gair Photographic Collection – Farming and livestock

Panel 7 – Charlie Gair Photographic Collection – Forestry